Olympian Capital Management's Renaissance

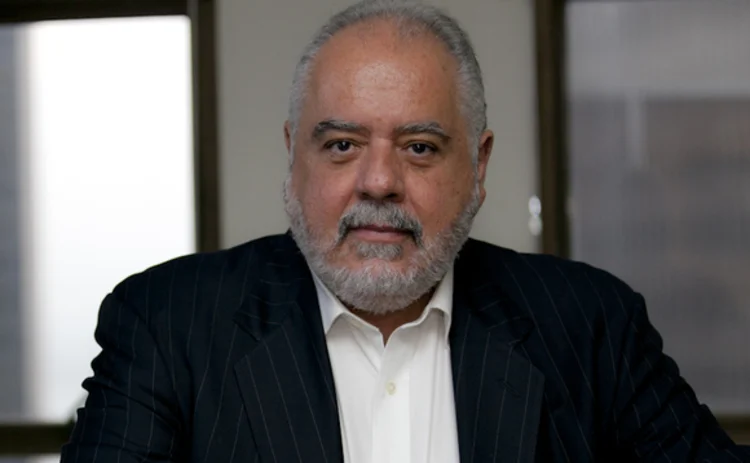

When Michael Levas looks at the markets, he sees music. Long before he founded Olympian Capital Management, he was a musician. He studied at the New England Conservatory and then at Berklee College of Music and tinkered with the saxophone, flute, clarinet and bassoon. He studied arrangements, composition and film scoring.

Like any future hedge fund manager, though, he enjoyed the idea of making money rather more than spending his life as a starving artist. So it wasn’t long before he stumbled into finance—and a music career was forever in his rearview mirror.

Though Levas no longer plays any instruments, he still sees music in everything around him: in the markets, on NYSE’s big board, and in profit-and-loss (P&L) and other reports.

“It got to the point where I kind of transitioned into finance because I loved it so much,” Levas says. “There are a number of musicians in the business. Former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, for instance, went to performing arts conservatory The Juilliard School. I think there’s a connection from watching the markets and looking at the charts. When you think about it, it’s kind of linear and musical—there’s a flow to it, which is very symmetric with the music business.”

Levas views Olympian, which harks back to his kitchen table in 2003, as a long, sweeping score, eight years in the making.

The People Equation

Levas acknowledges that there were mistakes—or at least, lessons to be learned—along the way. From Olympian’s humble beginnings in Levas’ Fort Lauderdale, Florida, home, through to 2007, he struggled with finding the right people and technology with which to surround himself. He had a vision of what he wanted, but reality was simply not matching the dream. Getting that “people equation” correct was proving more challenging than he had anticipated. So Levas decided to clean house and start anew.

“I realized that in order for me to go forward and realize my dream, I really needed to bring in superior quality people, and to be very specific in knowing who and what to target,” Levas says.

First, he went out and nabbed Evelyn Journet to run Olympian’s administration. And earlier this year he tapped Mark Krill as Olympian’s chief marketing officer.

But since Olympian is an investment firm, the puzzle wasn’t complete until Levas coaxed Arun Kaul, a co-founder of Hillsdale Investment Management, to join him at Olympian, where their minds and trading experience combined to bring about a renaissance, as Levas describes it.

“I really felt that our weakness as a firm—and I’m being very honest here—was that I didn’t have a sales and marketing person and I didn’t have an equal, someone like Arun, next to me,” Levas says. “By bringing in Mark and Arun, we are now making the weakness our strength so that we can go forward and be the firm that I envision us to be.”

Levas gave up his title as chief investment officer and handed over the operational side of the business to Kaul, who started at the firm this past September.

Back in 1996, Kaul joined forces with Christopher Guthrie to start Hillsdale. The two opened the fund with $2 million under management, which, over the next 15 years, grew to more than $500 million. When Hillsdale, based in Toronto, started, it was almost entirely focused on alternative strategies. But by 2011, the firm had shifted to become an almost exclusively long-only shop.

Kaul wanted to be in the alternatives space—he views it as a better way to manage money in terms of being able to hedge positions and move market exposures accordingly. He spent the next year or so testing the waters and meeting with hedge fund managers and a number of endowments.

Kaul and Levas had known each other for a few years after meeting at a conference at Harvard University. They had kept in touch and over dinner in New York City, Levas offered Arun the opportunity to swap chilly Toronto for sunny South Florida. They spent the next three months discussing their investment strategies, and found they had complementary trading skill sets.

“There was a motivation to do something different,” Kaul says. “I wanted to be involved in growing a firm as opposed to only focusing on the money management side. There aren’t a lot of those kinds of opportunities and it’s contingent on the partner and being able to get along with that person.”

The Tech Equation

Kaul has also been integral in upgrading Olympian’s technology. While at Hillsdale, he had built everything and rarely employed the help of third parties. But at Olympian, a firm that has less than $100 million under management, according to Levas, the team decided that it would be best to tap into the vendor community to build a multi-asset trading platform.

“In my previous life, we built everything—risk management, portfolio management, research, and trading and execution, which is the hardest part to build in terms of keeping up with the new technologies and straight cost,” Kaul says.

“Here, it was a pure business decision to outsource the technology and not build in-house because it’s a huge commitment—you can’t half-build something,” he says.

Levas and Kaul wanted to create a firm that could trade everything: equities, credit, commodities, options, fixed income, foreign exchange and so forth. As Kaul puts it, there will be times when Olympian will not be trading in equities simply because there are better options out there.

In order to build its new trading platform, Olympian tapped into Interactive Brokers, its prime broker, and Merrill Lynch for the engine and Knight Capital for some of its interfaces. Kaul says it was important for the firm to be able to trade in multiple asset classes without having to lose latency by switching systems.

Also, from a risk management and reporting perspective, having one system is a key part of building a trading platform where all the data is aggregated in as streamlined a manner as possible, supporting efficient analysis, which can, in turn, be provided to regulators and investors when necessary. Not only is Olympian a complex firm in the sense that it trades multiple asset classes and employs a number of different strategies, but it also dabbles in high-frequency and algorithmic trading and has a strong direct market access (DMA) presence.

Kaul says the platform is about 85 percent complete and that there will continue to be tweaks made to the system as the fund grows.

“You don’t have to build everything in terms of a perfect structure from day one—you can gather from different sources,” he says. “But the caveat is that you have to have the proper experience, the proper know-how, and you need to know what you are looking at.”

The New Year

Levas views 2012 as a tremendous year of opportunity for Olympian, despite all the uncertainty that exists in Europe and with regulations at home and abroad. He says that with the right people finally in place, and a platform that can handle the firm’s multi-asset ambitions, Olympian is ready to capitalize on investor wariness that began in 2008.

“This is a great opportunity for the business,” he says. “I believe that because of what’s happened since 2008, all these problems that have faced the industry, even up to the collapse of MF Global, this is a great opportunity for us because people come in and see that you’re legit. They’re going to respect that and they’re going to want to be a part of that. People in our business are tired of being treated like a number.”

This year, Olympian will look to continue to evolve its platform and data portals, in addition to opening a New York office, with an eye toward Europe and Asia in the near future, Levas says. After making a significant investment in technology and human capital in 2011, the firm will continue to look to expand its staff in order to make a significant leap in growth in the New Year.

The Sunshine Equation

Fort Lauderdale might not seem like a logical place to start a hedge fund. And even Levas acknowledges that the choice of South Florida was somewhat arbitrary. After leaving Lehman Brothers back in 2001, he took some time off. He had always had an itch to start something on his own and after getting tired with retirement—in only a few short months—he decided that he would start seriously thinking about how he would build a hedge fund from the ground up.

As a kid, Levas had spent some time with his family down in Fort Lauderdale and he had even recently bought a summer condo there. But he was, at the time, settled in Boston with his wife. Then, one bitterly cold Massachusetts winter’s day, while in Harvard Square standing at a street corner waiting to cross, a car flew by and sprayed him with slushy snow. He grabbed his cell phone, called his wife, and said: “Let’s move down to Florida.”

When Levas arrived, he found that there were many notable investment firms already putting down roots. The evolution of technology also helped break down barriers that the firm might have faced if it had tried to open there in 1990.

“If we are going to excel at what we do and be the smartest firm in South Florida, we need to have the technological ability to be exactly that,” Levas says. “We trade all asset classes—equity, fixed income, commodities, futures, FX—so we need to be able to do that very effectively, very efficiently, and quickly. With technology being what it is, we can do business from anywhere—we don’t have to be in New York, Boston or London.”

If Olympian evolves into the success that Levas envisions, it will look something like what Highbridge Capital Management has become. Highbridge began with Glenn Dubin and Henry Swieca and grew from $35 million in capital back in 1992 to the $21 billion giant it is today.

Levas feels that now that he has the right mix of people in place—with Levas and Kaul playing the roles of Dubin and Swieca—and with his multi-asset trading platform up and running, Olympian, too, can achieve that level of success.

“Having the firm and seeing what it’s grown to and seeing what we’re doing, is extremely exciting,” Levas says. “I can envision it one year from now, three years, five years and 10 years from now, and I’m really excited by what I see.”

Levas bristles at the thought of Olympian being sold one day to a bigger fund for the sheer sake of profit. This is, for him—and now Kaul—a legacy. They view this firm as being something closer to the glory days of a Goldman Sachs prop trading desk; Kidder, Peabody & Co.; or DLJ.

“It’s seeing the name and building it,” Levas says. “It’s about building a quality organization that will last far beyond my lifetime—that’s what I’m interested in doing.”

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Emerging Technologies

Man Group CTO eyes ‘significant impact’ for genAI across the fund

Man Group’s Gary Collier discussed the potential merits of and use cases for generative AI across the business at an event in London hosted by Bloomberg.

BNY Mellon deploys Nvidia DGX SuperPOD, identifies hundreds of AI use cases

BNY Mellon says it is the first bank to deploy Nvidia’s AI datacenter infrastructure, as it joins an increasing number of Wall Street firms that are embracing AI technologies.

This Week: Linedata acquires DreamQuark, Tradeweb, Rimes, Genesis, and more

A summary of some of the latest financial technology news.

Systematic tools gain favor in fixed income

Automation is enabling systematic strategies in fixed income that were previously reserved for equities trading. The tech gap between the two may be closing, but differences remain.

Euronext microwave link aims to cut HFT advantage in Europe

Exchange plans to level playing field between prop firms and banks in cash equities with cutting edge tech.

Why recent failures are a catalyst for DLT’s success

Deutsche Bank’s Mathew Kathayanat and Jie Yi Lee argue that DLT's high-profile failures don't mean the technology is dead. Now that the hype has died down, the path is cleared for more measured decisions about DLT’s applications.

‘Very careful thought’: T+1 will introduce costs, complexities for ETF traders

When the US moves to T+1 at the end of May 2024, firms trading ETFs will need to automate their workflows as much as possible to avoid "settlement misalignment" and additional costs.

Waters Wrap: Examining the changing EMS landscape

After LSEG’s decision to sunset Redi, Anthony examines what might lie ahead for the EMS space.

Most read

- Sell-Side Technology Awards 2024: All the winners

- Systematic tools gain favor in fixed income

- Sell-Side Technology Awards 2024: Best sell-side front-office platform—Bloomberg