A network of Cusip workarounds keeps the retirement industry humming

Restrictive data licenses—the subject of an ongoing antitrust case against Cusip Global Services—are felt keenly in the retirement space, where an amalgam of identifiers meant to ensure licensing compliance create headaches for investment advisers and investors.

Data licenses from Cusip Global Services (CGS)—and the things they do and do not permit—sit at the heart of an ongoing federal court case in the Southern District of New York. Recent witness testimony by a Texas-based fiduciary firm, Leafhouse Financial Advisors, detailed a complex network of identifiers used in the retirement industry—from Cusips, Isins, and tickers, to SecIDs, FIGIs, and other proprietary identifier schemes.

The gold standard for uniquely identifying North American stocks and bonds, the alphanumeric Cusips function similarly to universal barcodes for securities. But unlike barcodes, Cusips are patented and copyrighted, and CGS maintains strict control of their use.

CGS tells its customers not to share its data with their own customers, creating a world of reference data “haves” and “have-nots.” Big firms are “haves”—the CGS licenses they hold mean they can freely pass Cusip information between themselves, while smaller firms that are not CGS license-holders cannot. For a “have” to communicate information about trades, orders, and funds to a “have-not,” it might create its own parallel system of identifiers; though most North American securities have a Cusip, it would also be assigned one of these parallel codes.

But each set of proprietary identifiers is different from the rest. For the CGS “have,” it’s simple—each Cusip maps to its own proprietary code. For the CGS “have-not,” it’s a nightmare—each security ends up with a host of distinct identifiers, maintained by the firm’s separate service providers.

Sources say this system of workarounds leads to messy historical records, manual reconciliations, quietly broken license agreements, and painstaking data audits—all of which add up to an unceasing fire drill exercise in data management.

CGS declined to comment.

Todd Kading, president and CEO at Leafhouse, testified that these substitute identifiers are created primarily by recordkeepers, large insurance firms whose role in the retirement industry is to process transactions, track employee contributions, and manage fund distributions.

As a fiduciary, Kading described the scenario of needing to create lineups—menus of funds in which participants are allowed to invest—on a single recordkeeper. The recordkeeper might create a fund with an alphanumeric code that is not a Cusip—for example, SV1—but outside of that recordkeeper’s walls, nothing inherently links SV1 to any underlying investment.

A fiduciary, which acts on an investor’s behalf, would need to further investigate SV1’s contents, perhaps finding that it leads to a low-volatility, generally safe, stable value fund. But a fiduciary managing a few thousand plans is likely to work with more than one recordkeeper. And another recordkeeper might use the same code—SV1—in its own investment menu. A fiduciary might easily conclude both are referring to the same fund.

“But, unfortunately, that’s not the case,” Kading said. “What happens is, that recordkeeper…may have put that as an identifier internally for federated small cap value R6”—a much riskier investment—“and that’s a problem.”

Data management woes are not specific to the retirement industry, and CGS is not solely responsible for the burdens there. But some of them are compounded by the firm’s licensing regime, the costs of which are sometimes passed onto investors, sources say. Providers of technology platforms and data services have provided relief over the years, but, of course, they are another cost.

In 2019, Broadridge acquired Fi360, a fiduciary-focused software platform that aims to help investment professionals document investment processes, evaluate products, and provide transparency into the retirement market.

The expense challenges faced by companies serving retirement plan advisers extend beyond rising proprietary fund identifier costs, including escalated costs of proprietary benchmarks, category statistics, and fund performance, says John Faustino, head of Broadridge Fi360 Solutions.

“Price increases associated with those required data elements represent some of the largest cost increases experienced over the last several years and are ultimately passed on to plan sponsors and plan participants,” Faustino says.

Advisers must cover those expenses to be profitable with the plans they serve, increasing their costs of doing business. Some of those costs are hard-dollar; others are administrative, like tracking distribution as required by some data providers. But quantifying these costs, especially at scale, is all but impossible.

CGS’s end-user license fee calculator maxes out at $518,138 annually for consuming more than 40,000 securities identifiers in four or more business lines in three or more regions. At the midpoint—up to 20,000 securities, two business lines, and two regions—the cost is $153,733 per year.

Waivers and discounts are offered according to firm size—US wealth managers with fewer than $5 billion in assets under management are eligible for a 100% discount on fees—or use case, such as for regulatory reporting only. Additionally, CGS says it will waive the license fee for an end-user customer who uses fewer than 500 identifiers over a 12-month period, but in this case, the customer will still need to obtain the license.

Some firms have gotten around these requirements by simply avoiding Cusip data either through alternative identifier schemes or by outsourcing certain functions to counterparties.

Alera Group is an independent national insurance and financial services firm based in Deerfield, Illinois. Its wealth division oversees more than $7.5 billion in assets under management, while its retirement division advises on about the same number of assets. It does not have a Cusip license because it does not need one, says Bob Jansen, director of investments for Alera Group Retirement Plan Services.

Alera is the product of a 2017 merger among 24 firms that created the nation’s seventh largest employee benefits firm and its fourteenth largest private insurance firm. But it offers securities through another company, Osaic Wealth, which has a CGS license that extends to its network of 11,000 independent broker-dealers and investment advisers.

At the time of the mega merger, Jansen, whose firm was the only one in the group that dealt with wealth management and retirement plan services, was tasked with deciding where to custody assets and which broker-dealer to use. He and his team tried to build out its own customer management software that would function like a Salesforce application. But they ran up against CGS’s data licensing barriers.

“These conversations kept coming up, and we realized that it was going to be more cumbersome for us to try and build it ourselves based on some of these limitations, versus just letting Fidelity [handle that],” Jansen says.

Fidelity was the firm’s sole wealth management custodian, while it was one of many recordkeepers that doubled as custodians on the retirement plans side.

“The data we have access to is at a higher level than where we would need to store Cusips in our system,” Jansen says. “And so, this was a problem that was presented to us, that we decided to solve by not solving it.”

On the retirement side, Alera uses RPAG, a retirement technology solutions provider, to collect, store, and access, client data at the plan level. RPAG was recently bought by Great Gray Group, a collective investment trust, or CIT.

In a December 2024 letter by Leafhouse to the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the fiduciary wrote that CITs, which are pooled investment vehicles managed by a bank or trust, display “Cusip dependency issues.” The popularity of these unlisted, exclusive investment vehicles has grown in recent years, reflecting a shift away from pricier mutual funds, according to EY.

Though cheaper and more flexible, CITs are also less transparent, partially owing to different regulatory standards. CITs, which are overseen by the Office of the Comptroller of Currency rather than the SEC, are mandated to have Cusips and usually lack tickers, which are typically free to use and view. In 2019, Nasdaq began assigning six-letter symbols to some CITs that choose to list on the Nasdaq Fund Network. However, both listing and registering for a ticker are voluntary for CITs, and only a small fraction of available CITs have done so.

As a result, Leafhouse wrote, the only reliable way to identify a CIT is via aggregators’ proprietary IDs or by using Cusips and its their associated paywall.

A source at a CIT says Leafhouse’s assertion “sounds right,” but does not see the lack of tickers for CITs as a significant burden on participants, with aggregators like Morningstar—a subscription to which is nearly ubiquitous in the retirement industry—covering much of the universe with not only IDs but rankings, quotes, returns, and other useful data points.

“I have not found retirement plan decision-makers to have any difficulty in obtaining access to the information they need in order to make investment decisions, whether it’s the [investment] manager or the responsible plan fiduciary, to select the investment funds they think should populate their lineup,” they say. “Nor have I seen any challenges with participants getting access to information about funds.”

But not all information is created equally.

“Oops!”

In Kading’s testimony, he said that when recordkeepers with CGS licenses are executing trades or communicating internally, they tend to use Cusips. But due to the licensing obligations, they must essentially police others if they are going to send them Cusips.

“If they are sending [Cusips] to you, they have to know whether or not you have a license, and if you don’t have a license, then they tend not to send them to you,” Kading said.

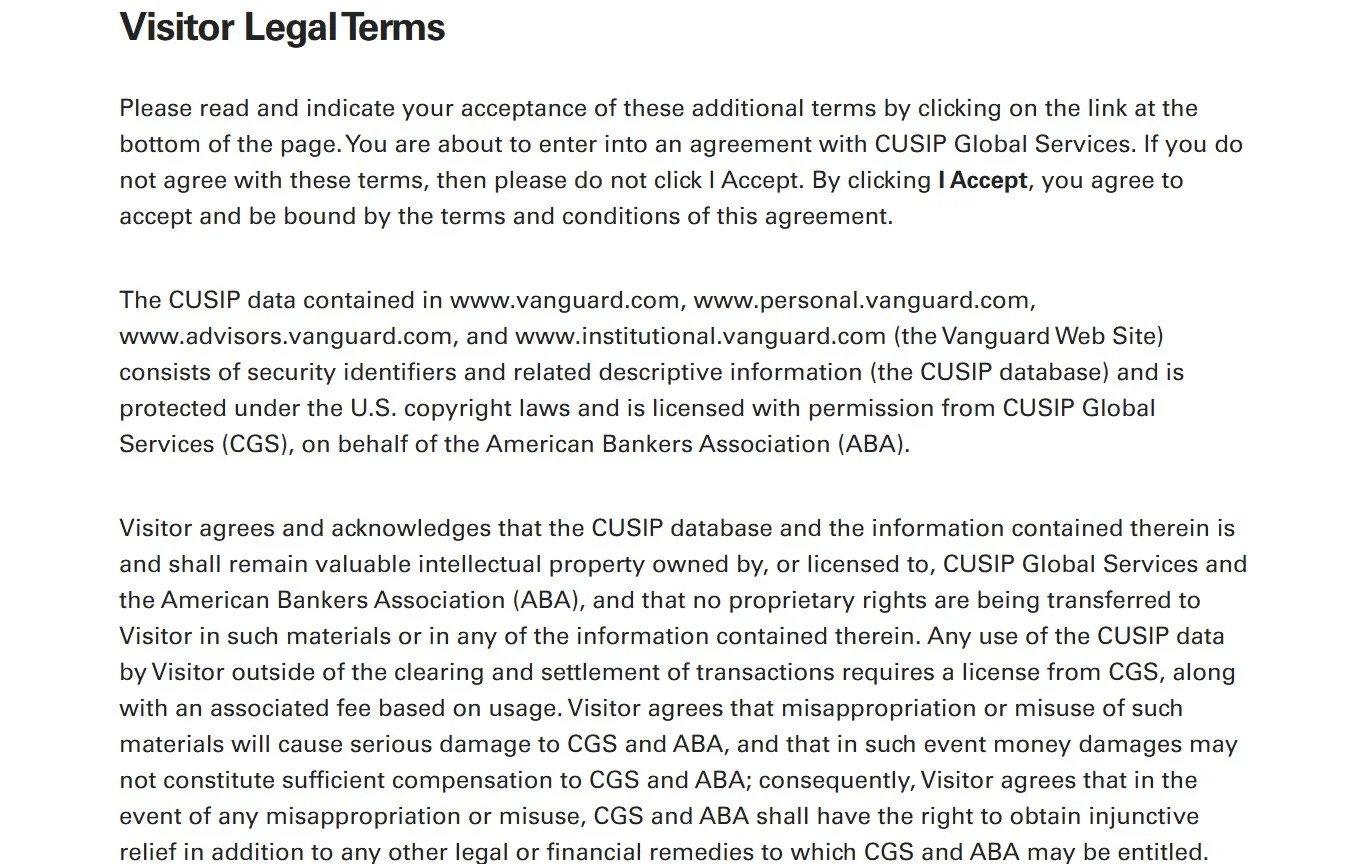

Even accessing some fund information on recordkeepers’ public websites prompts warnings that viewers are about to enter into an agreement with CGS. For example, to view holdings details for VMRXX, Vanguard’s Cash Reserves Federal Money Market Fund Admiral Shares, visitors must agree to terms and conditions that state any use of Cusip data outside of the clearing and settlement of transactions requires a license from CGS, along with an associated fee based on usage.

A visitor must also agree to not publish or distribute any substantial portion of the Cusip database, nor summaries or subsets thereof to any person or entity. Visitors also may not create or maintain a master file or database of Cusip identifiers or descriptions for itself or any third-party recipient that is intended to serve as a substitute for any Cusip service.

Fidelity, the largest retirement industry recordkeeper by participants and assets, is an example of a firm that uses a combination of tickers and internally developed alphanumeric fund codes for its publicly listed investment options. A spokesperson for Fidelity declined to comment.

“You can see how there are likely to be overlapping fund codes between various uncoordinated ID systems,” Dale Homburg, senior vice president of digital innovation at Leafhouse, tells WatersTechnology.

A source at a major US recordkeeper agrees with Kading’s characterization.

“They can’t redistribute; this happens with a lot of players. Because [counterparties] don’t have downstream licenses—and you don’t want to swallow the costs on behalf of them—you created another translation system in order to avoid licensing costs,” they say.

But a problem solved sometimes leads to new problems. Recordkeepers prefer their downstream non-licensed counterparties to use the recordkeepers’ own internal taxonomies to communicate fund change orders. Scaled out, that means a firm using 20 recordkeepers can use up to 20 different languages to buy and trade the same instruments.

As counterparties, fiduciaries must maintain the various parallel code systems in their security masters. Sometimes code systems are even different per fund menu or platform at one recordkeeper.

Apart from the data management and reconciliation exercises that must be undertaken by recipient firms, it doesn’t help matters of uniformity that this system is not always enforced. The recordkeeping source says there is a “gray area,” where recordkeepers sometimes must weigh their obligations against client demands.

“If the plan sponsor basically says, ‘No, I want the Cusips and everything else,’ and they’re a $50 billion pension plan, what do you do?” they ask.

Recordkeepers collect fees twice, both from recordkeeping itself and from fund management. If it were to lose a $50 billion pension fund, it would be a direct hit on its revenue in more than one way.

“A lot of retirement recordkeepers bend over backward on what your plan sponsor might be asking for,” the source says. “I hate to call it a blatant violation of your license agreement, but this is like a semi-enforcement scenario. An ‘oops!’ type of scenario.”

And because each identifier system is unique to each recordkeeper, recordkeepers identify the same funds by different names, or different funds by the same names—a common pain point for firms that employ multi-recordkeeper strategies to manage thousands of plans.

“You might be offering some overlapping funds on different platforms. And maybe you chose Empower and [Charles] Schwab as your two providers, and they have a different translation of what ends up being the same Vanguard fund,” the recordkeeping source says.

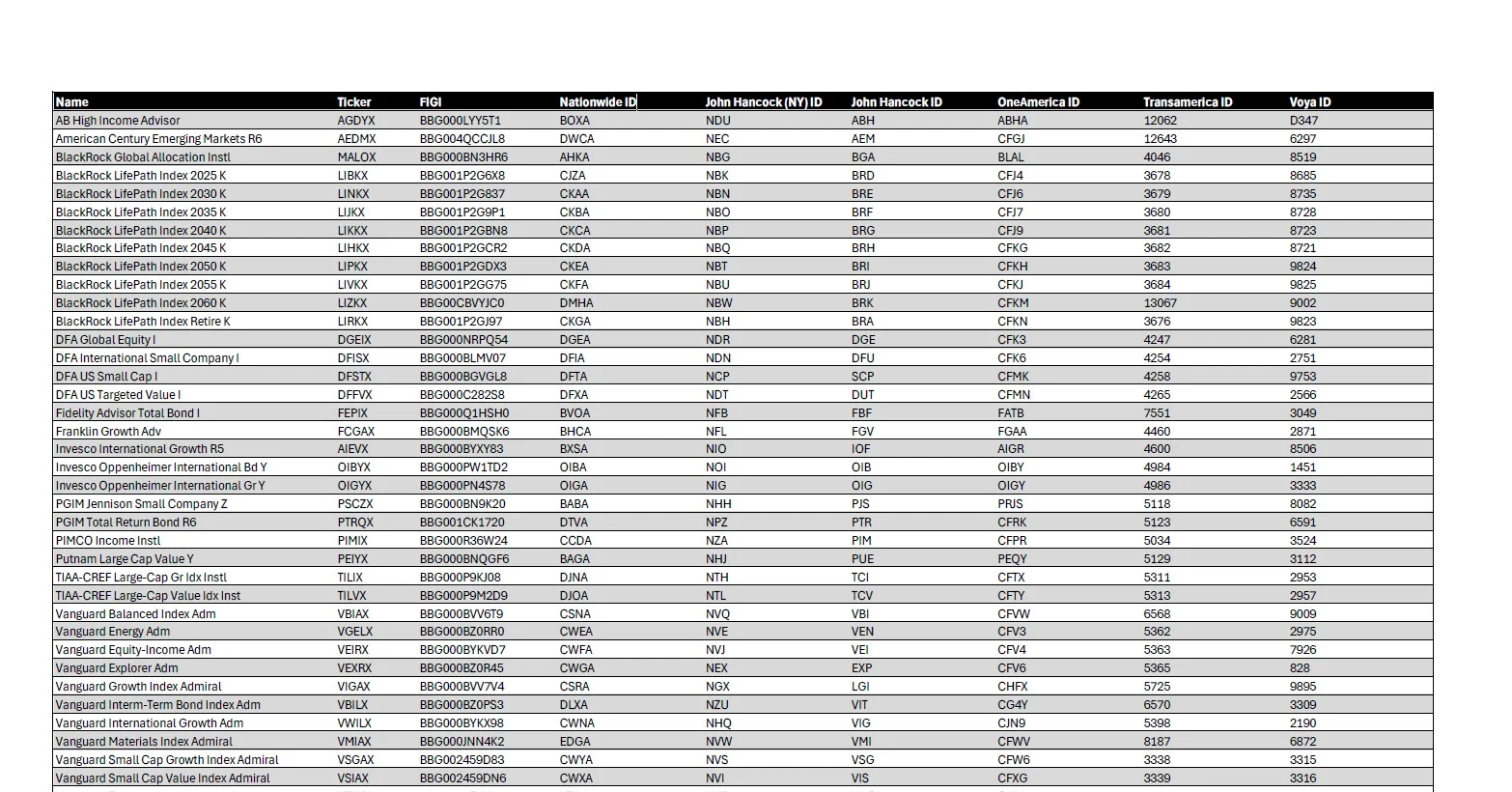

As an example of these taxonomies, the ticker for BlackRock Global Allocation Instl is MALOX. Its Cusip is 09251T509. Its FIGI is BBG000BN3HR6. But Nationwide calls it AHKA. John Hancock calls it BGA. OneAmerica calls it BLAL. Transamerica calls it 4046. And Voya calls it 8519. A fiduciary, manager, or adviser using each of these recordkeepers would need to know that each of these IDs corresponds to the same underlying fund to make trades across its various recordkeepers.

Nationwide and OneAmerica did not respond to a request for comment. Transamerica declined to comment. Voya did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

A spokesperson for John Hancock says that in the retirement industry, the firm operates as both a custodian and a recordkeeper, and it offers a variety of proprietary and third-party investment products. Internally, the firm uses Cusips and tickers, but it also uses an in-house identifier, the taxonomy for which includes BGA for BlackRock’s Global Allocation Fund, to link fund data across systems and databases. Externally, it uses tickers and fund names in client communications and investment literature.

“We utilize a variety of identifiers including Cusip, [Morningstar] SecID, ticker, ISIN—it depends on who we are communicating with and through which medium. Trading, reconciliation, and pricing processes are highly reliant on the Cusip as the identifier,” the spokesperson says.

The firm did not comment on whether John Hancock requires some firms to use their proprietary fund codes for trades, adds, and change orders, and whether John Hancock has ever cut off a recipient firm’s access to Cusip numbers based on the recipient not having a CGS license.

Utility’s futility

In finance, subpar data practices are par for the course, to the point where data management itself is a cottage industry with a wealth of vendors, consultancies, and applications that promise to help.

Last year, a US broker-dealer shared with WatersTechnology a letter it received from CGS, which threatened to turn off the firm’s access to Cusip numbers if it did not sign a license agreement with the data provider. A source at the broker-dealer said the firm had not received any Cusip data from CGS itself but through one of CGS’s authorized re-distributors—a different entity from a recordkeeper, which is an end-user.

A source with knowledge of Cusip’s licensing policy said at the time that enforcement actions like these letters are triggered when end-users are found to be bulk downloading Cusips, typically to the tune of 1,000 or more. Authorized re-distributors—for example, Bloomberg—are required to provide usage metrics to CGS on a periodic basis, at which point CGS assesses the data consumption and use-cases of firms that both do and do not have signed contracts with itself.

CGS data audits of both licensed and unlicensed firms are routine. Typically, the recordkeeper source says, the offending firm settles by paying CGS several thousands of dollars “to go away” for that period. Litigation, which would cost even more, is “just not worth it.”

The Investment Adviser Association, a US non-profit organization for fiduciary investment advisers, first raised concerns about Cusip licensing and other practices—including fees, audits of all uses by end-users, and other “unfair” terms and conditions regarding advisers’ ability to maintain Cusips in their database and the use of Cusips to identify securities in marketing materials—with the SEC in 2010.

The IAA reiterated its concerns again last fall in another letter written by Gail Bernstein, general counsel and head of public policy, to the SEC.

“Most IAA members and other end-users of Cusip are charged substantial commercial licensing fees that demonstrate no regard for the identifier’s public service origins or the public utility purposes of its many uses. CGS has no accountability or regulatory oversight, and its fees appear disconnected from the cost of maintaining the identifier,” the letter reads. “CGS can now cut off any investment adviser’s access to its data feed, and, thereby, to its ability to serve its clients, meet its regulatory obligations, and otherwise conduct its business.”

It would be inaccurate to say that CGS bears the main responsibility for the existing system of conflicting IDs that permeate the retirement industry, but its licenses play a part in upholding it.

Cusip has been the yardstick for North American securities identification for more than half a century. The standard is owned and patented by the American Bankers Association, while CGS is operated by FactSet, which acquired the service bureau from S&P Global in 2022. A de facto industry utility, it brought needed standardization and digitization to a market that, prior to its existence, had no reliable, consistent way to deliver securities and maintain records.

In October, global head of CGS, Scott Preiss, wrote a letter to the SEC touting the advantages it has offered trading, settlement, custody, and overall market security over the years.

“Cusip’s central role is due to its enormous success in the marketplace. Cusip has long served the markets efficiently in a number of different functions, from trading, clearance and settlement to risk monitoring to regulatory reporting,” he wrote.

The letter, like Leafhouse’s, was in response to US financial regulators’ proposed rules under the Financial Data Transparency Act, which suggested last year to make the FIGI the exclusive securities identifier in regulatory reporting, over the Cusip and its European counterpart, the ISIN. But many industry stakeholders were not sold on the idea.

Conflicting standards—or no standard at all—that confuse and burden users is a direct reason and justification for Cusip’s existence. But in the retirement industry, it appears the solution itself is part of the problem.

Further reading

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: https://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Data Management

Digital employees have BNY talking a new language

Julie Gerdeman, head of BNY’s data and analytics team, explains how the bank’s new operating model allows for quicker AI experimentation and development.

Can mastering data solve AI’s cognitive dissonance?

The IMD Wrap: Bank execs are still bullish on AI, but recent studies suggest it’s not the panacea they’re making it out to be. Can the two views be rectified?

Everything you need to know about market data in overnight equities trading

As overnight trading continues to capture attention, a growing number of data providers are taking in market data from alternative trading systems.

AI strategies could be pulling money into the data office

Benchmarking: As firms formalize AI strategies, some data offices are gaining attention and budget.

Identity resolution is key to future of tokenization

Firms should think not only about tokenization’s potential but also the underlying infrastructure and identity resolution, writes Cusip Global Services’ Matthew Bastian in this guest column.

Vendors are winning the AI buy-vs-build debate

Benchmarking: Most firms say proprietary LLM tools make up less than half of their AI capabilities as they revaluate earlier bets on building in-house.

Private markets boom exposes data weak points

As allocations to private market assets grow and are increasingly managed together with public market assets, firms need systems that enable different data types to coexist, says GoldenSource’s James Corrigan.

Banks hate data lineage, but regulators keep demanding it

Benchmarking: As firms automate regulatory reporting, a key BCBS 239 requirement is falling behind, raising questions about how much lineage banks really need.